A Layman’s Guide to Navigate a Climate ‘Crisis’ - Part 4

Volume 4 / Special Issue / 4. Public Enemy No. 2 – Fossil Fuels

Well Hello!

If you missed the previous post, 3. Public Enemy No. 1 – CO2, the link below will take you to it to put things into context.

4. Public Enemy No. 2 – Fossil Fuels

In the first part of the section, the contents follow a specific order. We first look at how oil forms, which literature is currently accepted among teaching institutions, and a summary of the existing theories, – we address concerns of fuel resources running out and what synthetic fuels are – we discuss what hydrothermal vents are and how they link to the alternative theories of how oil forms (abiogenesis) – finally we turn to the textbooks to review the laws of thermodynamics.

In the second part of the section, we talk about the green initiative, electric cars, and alternative electricity generation.

4.1 What are Fossil Fuels and How Does Oil Form?

According to the National Geographic, fossil fuels are made from decomposing plants and animals. It is further quoted: “Oil is originally found as a solid material between layers of sedimentary rock, like shale. This material is heated to produce the thick oil that can be used to make gasoline. Natural gas is usually found in pockets above oil deposits. It can also be found in sedimentary rock layers that don’t contain oil. Natural gas is primarily made up of methane.”

Fossil fuels according to Petro Wiki, are found in the Earth’s crust of which coal, oil, and natural gas are examples. Petro Wiki also notes that the source of petroleum is plants and animals that died millions of years ago during which this high carbon content matter was exposed to high pressure and temperature that caused them to become mature and generate petroleum. They however also note: “the processes that lead to the generation of petroleum are still not clear enough”.

According to the University of Calgary, oil or petroleum is a readily combustible fossil fuel that is composed mainly of carbon and hydrogen and is thus known as a hydrocarbon. As quoted: “the formation of oil takes a significant amount of time with oil beginning to form millions of years ago. 70% of oil deposits existing today were formed in the Mesozoic age (252 to 66 million years ago), 20% were formed in the Cenozoic age (65 million years ago), and only 10% were formed in the Palaeozoic age (541 to 252 million years ago). This is likely because the Mesozoic age was marked by a tropical climate, with large amounts of plankton in the ocean.”

4.2 Biogenic Theory and Abiogenic Theory

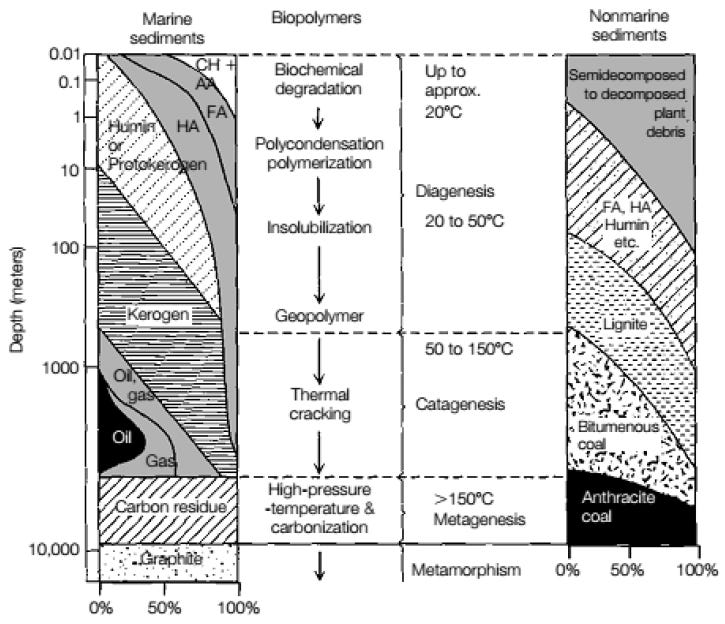

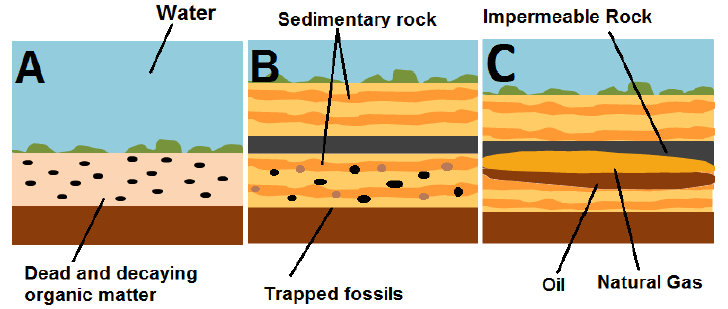

The leading theory (“biogenic theory”), therefore, is that dead organic material accumulates on the bottom of the oceans, riverbeds, or swamps, mixing with mud and sand where over time, more and more sediment piles on top and the resulting heat and pressure transforms the organic layer into a dark and waxy substance known as kerogen. The kerogen molecules, if left alone, will eventually crack, breaking up into shorter and lighter molecules composed almost solely of carbon and hydrogen atoms. Depending on how liquid or gaseous this mixture is, it will turn into either petroleum or natural gas. This theory was first proposed by a Russian scientist almost 250 years ago.

In the 1950s this ‘traditional theory’ was questioned where a few scientists proposed that petroleum could form naturally deep inside the Earth. This was called the “abiogenic theory”.

One hypothesis was that petroleum might seep upward through cracks formed by asteroid impacts to form underground pools. Others suggested that ancient impact craters should be probed for oil.

Abiogenic sources of oil have reportedly been found in parts of the world, but never in commercially profitable amounts.

If abiogenic petroleum sources are indeed found to be abundant, it would mean Earth contains vast reserves of untapped petroleum and, since other rocky objects formed from the same raw material as Earth, that crude oil might exist on other planets or moons in the solar system, scientists say.

4.3 Fossil Fuel Resources Running Out

Many claim that fossil fuels are running out and can no longer be a ‘sustainable’ or ‘clean’ source of energy. Hence the big movement towards ‘renewable’ energy.

The answer to the question “Is the world running out of oil?” could be simplified to a basic “no,” but it’s rather more complicated than that. There are several different ways to categorise oil, from proved reserves to those that are technically recoverable. And even these don’t all describe how much oil might sit beneath the surface of the Earth.

According to the British Petroleum’s 2019 Statistical Review of World Energy, the total proved reserves of the planet’s oil at that time was 1,733.9 billion barrels. Yearly global consumption in 2019 was about 35.9 billion barrels. A basic calculation reveals that if proved reserves didn’t grow, and if consumption remained constant at 2019 levels, it would take only about 48 years — meaning some time in 2067 — to exhaust those reserves. The trouble is, proved reserves only represent the oil that a given region can theoretically extract based on the infrastructure it has planned or in place.

In other words, technology has a big impact on what’s considered a proved reserve. Advancement in technology and geological knowledge, increases the estimates of technically recoverable resources through time, this is according to the spokesperson for the American Petroleum Institute.

Meanwhile, much like groundwater, the undiscovered technically recoverable resources, exist based on geology, geophysics, geochemistry, and familiarity with similar basins and rock formations. These are yet to be discovered according to the USGS.

Furthermore, the production of oil depends on demand, and the development of technology. Thus, the question that should be asked: “How long will we want it and at what price?” Alternative sources of fuel like natural gas or renewable energy are eating into the demand for oil.

Proved reserves will always be fluctuated with demand, as demand dictates the price. If the price is high enough, the cost of extraction would be worthwhile.

So, to summarise, how much oil there is will depend on the price, but how much demand there is will also depend on the price. Pictures below show oil bubbling and free flowing in the desert.

4.4 Synthetic Fuel

It should be said that scientists still don't know for sure where oil comes from, how long it takes to make, or how much there is.

German inventors, Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch invented a way to synthesise abiotic (non-biological) oil during World War II for the German war effort. Now known as the Fischer-Tropsch (FT) process is a gas to liquid (GTL) polymerization technique that turns a carbon source (coal) into hydrocarbons chains through the hydrogenation of carbon monoxide by means of a metal catalyst. Simply put, carbon monoxide (CO) + hydrogen (H2), combined known as syngas, + metal catalyst (usually iron, nickel, or cobalt) = liquid hydrocarbons / synthetic fuel.

The carbon source is converted to syngas through a process of gasification (C + H2O → CO + H2) where a controlled flow of steam and oxygen is maintained through the source at high temperature and pressure (1200°C – 1400°C and 3 MPa).

Did You Know?

The world's largest scale implementation of Fischer–Tropsch technology is a series of plants operated by Sasol in South Africa, a country with abundant coal reserves, but little oil. With a capacity of 165,000 barrels per day (Bpd) at its Secunda plant. The first commercial plant opened in 1952. Sasol uses coal and now natural gas as feedstocks (sources of carbon) and produces a variety of synthetic petroleum products, including most of the country's diesel fuel.

PetroSA, operates a refinery with a capacity of 36,000 barrels a day plant that completed semi-commercial demonstration in 2011, paving the way to begin commercial preparation. The technology can be used to convert natural gas, biomass, or coal into synthetic fuels.

4.5 Hydrothermal Vents aka Smokers

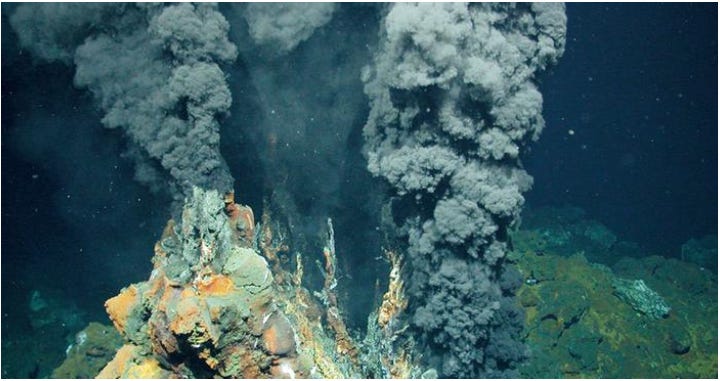

Hydrothermal vents form at locations where seawater meets magma. Many faults and cracks along the ocean ridge allow cold sea water to penetrate deep into the crust, possibly as much as 6 km, where it meets hot rock and is heated to temperatures of up to 450°C. The hot water reacts chemically with the surrounding rocks, changing their composition. The hot water in turn leaches silica, sulphur, and metals such as copper zinc, lead, iron, manganese, gold, and silver from the rocks, and takes them into solution. The resulting hot, metal-charged water, termed hydrothermal fluid, rises upwards through cracks, and emerges on the sea floor to form hot springs, while more cold sea water is drawn into the surrounding rocks in order to replace it.

The hot liquids do not boil due to the high pressure exerted by the overlying body of water. As the hot fluid meets the cold sea water, metal sulphides and other compounds (particularly silica) precipitate, forming clouds of fine particles. As a result, these hot springs are termed ‘smokers’.

Some of the particles stick together to form a chimney around the hot spring, but most settle on the ocean floor in the surrounding area. These smokers provide homes for unique forms of life adapted to this harsh environment. These organisms form part of a complex ecosystem fed ultimately by bacteria that derive their energy from the chemical imbalances between the hot, mineral-rich spring water and the surrounding sea water.

4.6 The Controversial Origins of Hydrocarbon Abiogenesis

In an article by Reeves & Fiebig titled “Abiotic Synthesis of Methane and Organic Compounds in Earth’s Lithosphere”, described the necessary geochemical signatures for abiotic (non-biological) light hydrocarbons to form within the Earth’s crust.

Theories of a deep, abiotic hydrocarbon production accompanied early petroleum discoveries in Russia in the late 19th century, as explained by Dmitri Mendeleev, and later by Soviet scientists and by the Austrian–born astrophysicist Thomas Gold (Glasby, 2006).

These scientists’ controversial theories suggested that economic hydrocarbons in geological crustal settings derive from abiotic CH4 (methane) that polymerised (a chemical process that combines several monomers to form a polymer or polymeric compound) to higher hydrocarbons in the mantle before migrating to Earth’s surface along deep faults.

It was noted in the article that theory and experimentation now support the idea that CH4 and other light hydrocarbons (containing 2 to 4 carbons) are stable at deep upper mantle conditions (beyond ~100−175 km depth) (McCollom, 2013). But it is questionable whether such deep mantle hydrocarbons would be able to transit the shallow upper mantle where CO2 becomes much more stable than CH4 owing to more oxidizing conditions (see McCollom 2013).

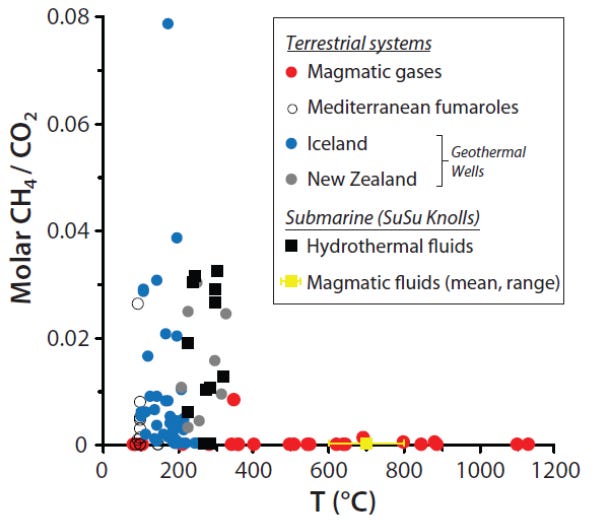

Degassing magmatic fluids (i.e., high-temperature volcanic gases) in terrestrial and marine volcanic settings are typically dominated by CO2 with only trace concentrations of CH4 (see Figure).

Lower temperature terrestrial geothermal and seafloor hydrothermal fluids (typically <450 °C) have higher CH4/CO2 ratios than magmatic gases. Abundant CH4 and lesser amounts of ethane, propane, butane, and other organics have been found in many rock-hosted crustal fluids, ranging from seafloor mafic/ultramafic hosted hydrothermal vents to low temperature terrestrial ophiolite springs, to ancient fluids sealed in cratons and igneous intrusions (McCollom and Seewald 2007; Charlou et al. 2010; Etiope and Sherwood Lollar 2013).

Many of these hydrocarbons are widely argued to form abiotically. Below magmatic/upper-mantle temperatures, at the reducing conditions encountered within oceanic or continental crust, reduction of CO2 to form hydrocarbons is thermodynamically possible.

4.7 What Do the Textbooks Say?

According to Cairncross, B. (2004), coal originates from peat, and if layers of peat are protected from oxidation and covered over with sediment and buried, the peat is gradually transformed into hard coal. The burial leads to compaction, dewatering and increased geothermal heat and pressure. All these processes cause progressive changes. Coal ranks from lowest to highest are peat lignite (brown coal), high-volatile bituminous coal, low-volatile bituminous coal, and anthracite. This progression reflects the increasing degree or effect of metamorphism. The higher the rank, the higher the carbon content, the less the water content and the lower the volatile matter content.

Minerals form through chemical reactions over a wide range of conditions, with temperature, pressure and chemical potentials of all components being the most important variables (Wenk, HR. & Bulakh, A., 2004). The principles of thermodynamics (as outlined below), developed in chemistry to quantify chemical transformations, are directly applicable to these reactions.

The first law of thermodynamics states that a change in the total internal energy of a system is equivalent to the heat transferred into the system minus the work performed by the system.

The second law of thermodynamics states that the heat absorbed by a system undergoing an irreversible process is not equal to the work performed on the system and part of the energy is always lost in the process and cannot be retrieved. Example: heat flows from the hotter body to the colder.

The third law of thermodynamics states that both internal energy and entropy characterise the state of a system, and they are independent of how that state has been reached. Example: all pure and perfectly ordered crystalline substances have the same entropy at absolute zero temperature.

Thus, decomposing organic material of any kind cannot deteriorate into a higher form of energy, this refers to the idea that decomposing organic material (such as shale and natural gas) can be turned into oil, as it violates the 2nd law of thermodynamics.

To briefly summarise: the 2nd law of thermodynamics says that high energy always becomes low energy, and the current leading biogenic theory of how oil forms suggest the opposite to be true – low energy to high energy, therefore, the 2nd law of thermodynamics is violated, and we must wonder if the theory is legitimate.

4.8 The ‘Green’ Initiative

There is of course a growing body of opinion that points out that the emperor has no clothes when it comes to all the fashionable green technologies. Electric cars, wind and solar power, hydrogen, battery storage, heat pumps – all have massive disadvantages, and are incapable of replacing existing systems without consequences.

Contrary to the claims of proponents of the Green New Deal and Net Zero, fossil fuels are the greenest fuels. Uniquely among energy sources, fossil fuel use emits CO2, which is the ultimate source of the elemental building block, carbon, found in all carbon-based life, i.e., virtually all life on Earth. The increased amplitude of the seasonal cycle in atmospheric CO2 and satellite-borne instrumentation to measure solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence from plants provide direct evidence that global photosynthetic activity (or Gross Primary Production, GPP, a measure of the change in global biomass) has increased over the past several decades (Frankenberg et al. 2011; Graven et al. 2013).

4.9 Electric Cars

Electric cars have been in existence since before internal combustion cars. They were taken off the market because they took a long time to charge, had a limited range and even in those times, were expensive and not practical at all. They have become widely available in the past 15 years due to advances in battery technology. Today, we have lithium batteries that don’t weigh as much, impressive, and powerful engine capacities and a bit longer ranges, but still takes a long time to charge.

The raw materials needed for a single battery needs at least 13 kg of lithium, 27 kg of cobalt, 59 kg of Nickel, 41 kg of copper, 86 kg of graphite, and roughly 227 kg of steel, aluminium, magnesium, plastic, and other materials. All of which are derived from mining. Manufacturers use large amounts of energy through processing, using fossil fuels.

According to a German study from researchers, Christoph Buchal, Hans-Dieter Karl, and Hans-Werner Sinn, for a Tesla battery of 75 kWh, means an additional CO2 emission of 10 875 kg to 14 625 kg of CO2.

Even after the initial production of the battery, many electric cars are charged by power plants that produce electricity by burning coal or gas. According to the US Energy Information Administration, 63% of total electricity generation in the United States is created using fossil fuels. If the electricity being used to power the electric cars is being produced using fossil fuels, then using electric cars is simply shifting CO2 emissions from the tailpipe of the car to the electricity power plant.

Quoted from a statement made in the New York Times:

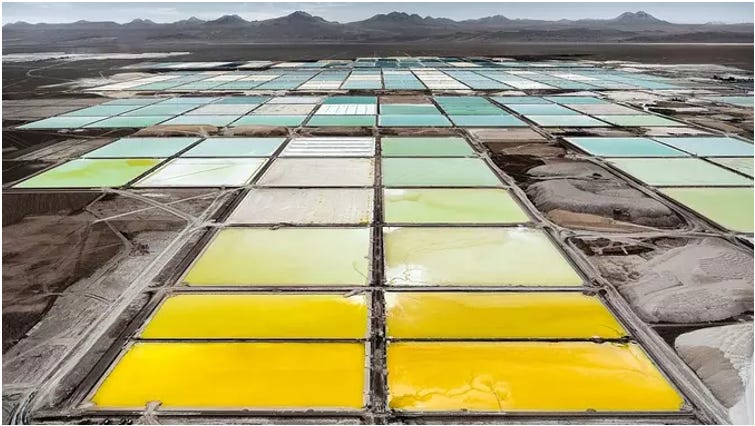

“Production of raw materials like lithium, cobalt and nickel, that are essential to EV technologies are often ruinous to land, water, wildlife and people.”

4.10 Physical Footprint of Various Electrical Generating Facilities

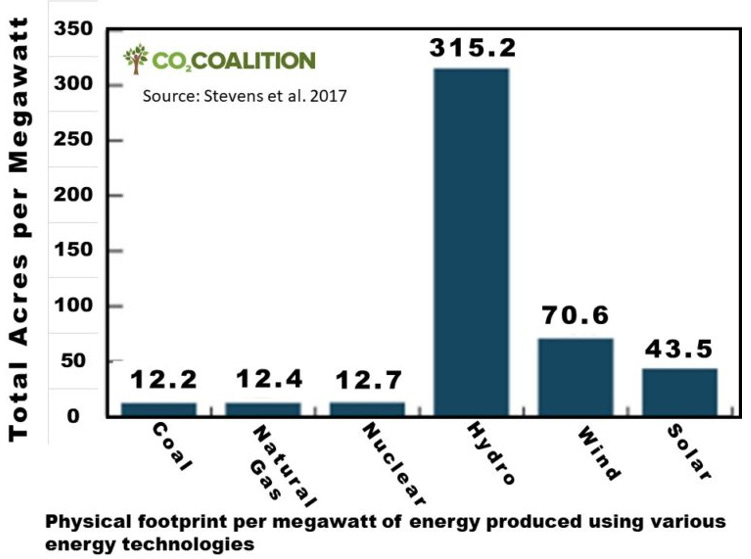

Different energy sources have different demands on land. The following figure compares the physical footprint needed to produce 1 megawatt (MW) of energy by the various energy technologies available. The estimates shown include direct and indirect land requirements based on U.S. practices as of 2015. They include estimates of land used during resource production, for transport and transmission lines, and store waste materials. Both one-time and continuous land-use requirements were considered (Stevens et al. 2017).

Compared to fossil fuels, solar would need more than three times as much land; wind, five times as much; and hydropower, 25 times as much.

To replace fossil fuel and nuclear generation, wind and solar would need to be coupled, at a minimum, with battery backup to provide electricity round-the-clock. The manufacture of batteries, as well as solar panels and wind turbines involves relatively vast quantities of metals and minerals. This necessarily entails equally vast mining operations and land disturbance.

Considering the supply chain and material availability for renewables are intermittent. The sun being semi-predictable and the wind being very unpredictable. Extensive wind droughts occur for months at a time and the reliance on wind has increased in recent years, but it won’t help if the wind is not blowing.

Although, the amount of mining would no doubt increase, the estimated global areal extent of mining operations is very small relative to agricultural operations thus, the additional amount of surface disturbance may be relatively minor. Agriculture depends substantially on the energy harvested from the sun while mining involves the excavation and processing (including transportation, smelting, and refining) of vast quantities of material (volume operations). Nevertheless, these operations themselves require substantial energy consumption and emit significant amounts of air and water pollution.

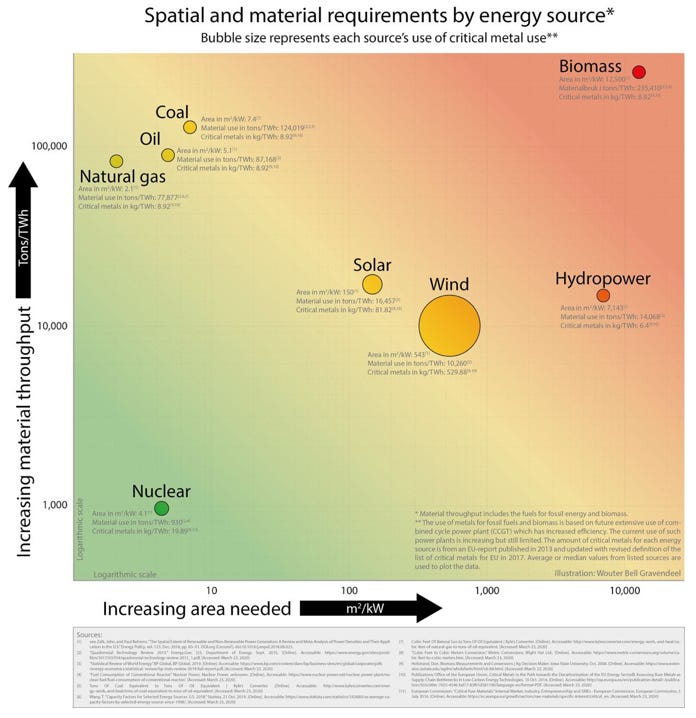

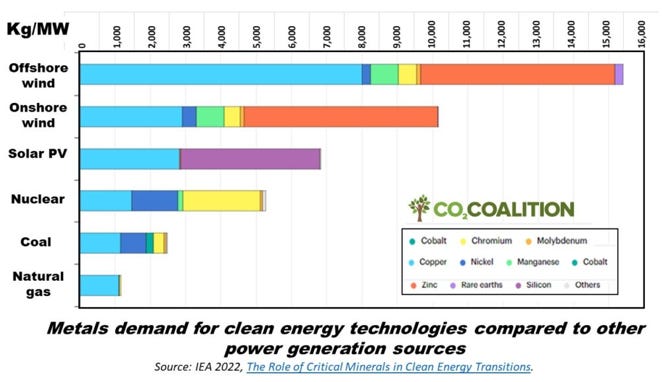

The International Energy Agency (2022) noted that solar and wind powered energy systems typically require more metals and minerals than their fossil fuelled analogues. It was noted that for instance, a typical electric vehicle requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a natural gas-fired power plant, while offshore wind plants require fifteen times as much as natural gas.

Figure below shows the demand estimated by the International Energy Agency for various metals to generate 1 MW of power using different energy technologies (IEA 2022). Clearly, the demand for these metals is substantially larger for renewable energy technologies. However, this figure excludes demand for concrete and cement, steel, and aluminium. Note: Lithium demand is included in the “rare earths” category. Source: IEA 2022.

Fossil fuels (natural gas and coal, in that order) have substantially lower demand for metals (and, therefore, associated land disruption), followed by nuclear, solar and, finally, wind.

Did You Know?

The European Commission, in February 2022, has declared natural gas and nuclear energy generation as ‘green’ and sustainable. Of course, some strings would remain attached. For example, gas plants could be considered green if the facility switched to renewable gasses, such as biomass or hydrogen produced with renewable energy, by 2035. Nuclear power plants would be deemed green if the sites can manage to safely dispose of radioactive waste. So far, worldwide, no permanent disposal site has gone into operation.

4.11 Nuclear Power

Nuclear power is a clean and efficient way of boiling water to make steam, which turns turbines to produce electricity.

Nuclear power plants use low-enriched uranium fuel to produce electricity through a process called fission—the splitting of uranium atoms in a nuclear reactor. Uranium fuel consists of small, hard ceramic pellets that are packaged into long, vertical tubes. Bundles of this fuel are inserted into the reactor.

A single uranium pellet, slightly larger than a pencil eraser, contains the same energy as a ton of coal, 3 barrels of oil, or 17,000 cubic feet (± 481 m2) of natural gas. Each uranium fuel pellet provides up to five years of heat for power generation. And because uranium is one of the world’s most abundant metals, it can provide fuel for the world’s commercial nuclear plants for generations to come.

Nuclear power offers many benefits for the environment as well. Power plants don’t burn any materials, so they produce no combustion by-products. Additionally, because they don’t produce greenhouse gases, nuclear plants help protect air quality. When it comes to efficiency and reliability, no other electricity source can match nuclear. Nuclear power plants can continuously generate large-scale, around-the-clock electricity for many months at a time, without interruption.

It also needs to be said that the above-described efficiency of nuclear power generation needs proactive management, and this is not necessarily a reality in South Africa at the moment.

Think About It…

The leading biogenic theory on how oil forms is problematic purely since it violates the second law of thermodynamics. The alternative abiogenic theory is promising as the hydrocarbons that form under these conditions are thermodynamically possible. PetroWiki acknowledged that the processes that lead to the generation of petroleum are still not clear enough.

As for fossil fuel availability in future, will depend on the price, and how much demand there is will also depend on the price.

What will be interesting to see in the coming future is what role synthetic fuels will play and where it will fit into the shift toward alternative energy, and as we have seen, is not in any way more environmentally friendly as advertised. Or maybe, the production of synthetic fuel can shed light on the geochemical processes that form fossil fuels in the earth’s crust?

One simply cannot attribute the change in climate of a whole Planet on single vectors alone. If CO2 can be the nominated scapegoat for these changes, then the following man-made actions should arguably also be in the running for the title.

Coming Soon - 5. Nominee No. 1 – Solar Radiation Management